The third principle of the rhizome in Deleuze and Guattari's A Thousand Plateaus is multiplicity. I'm still struggling with this concept, but I am forming a clearer image of what it means for me and my classes.

Each person in a class, students and teacher, is a rhizome, a multiplicity, and as such, they are not reducible to a single term such as student or teacher, though that reduction may have some temporary utility as a convenient shorthand. Deleuze and Guattari note this convenience in their witty opening to ATP: "Why have we kept our own names? Out of habit, purely out of habit. … To render imperceptible, not ourselves, but what makes us act, feel, and think. Also because it's nice to talk like everybody else, to say the sun rises, when everybody knows it's only a manner of speaking. … We are no longer ourselves. Each will know his own. We have been aided, inspired, multiplied" (ATP, 3). Isn't that clever? A name serves not to reveal us to others but to hide us, "to render imperceptible … what makes us act, feel, and think."

How does a name do that? By reducing the multiplicity of any person to a single point, a label, a name that deceives us into the belief that we know that person if we know their name. All names, even numbers, are expedient fictions, a shorthand that allows us to quickly navigate the world, but we must always be watchful, sensitive to the multiplicity clustered about the pinpoint of each name. "The number is no longer a universal concept measuring elements according to their emplacement in a given dimension, but has itself become a multiplicity that varies according to the dimensions considered (the primacy of the domain over a complex of numbers attached to that domain). We do not have units of measure, only multiplicities or varieties of measurement" (ATP, 8). When we say that this is John, an A student, and this is Mary, an F student, then we have reduced complex multiplicities to a few features in a very narrow context.

Neither is course content reducible to a few bullet points on a PowerPoint. Like people, knowledge is a multiplicity, connected to all else, and any boundary between this knowledge and that is, at best, an expedient fiction. As teachers, we must be most sensitive to the connections between knowledge and our students, recognizing that each connection is likely different, a multiplicity of connections. Each student is an assemblage of unique intellectual, emotional, social, sexual, religious, economic rhizomes that interconnects and interplays with the course content rhizome in its own unique way, and then that resulting assemblage interconnects more or less with all the other class assemblages, including the teacher's, to create a unique class assemblage that makes this ENG 1101 course different from any of my other ENG 1101 courses now, past, or future.

This reminds me of Shunryu Suzuki's wry comment in his book Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind: "In the beginner's mind there are many possibilities, in the expert's mind there are few." I don't believe that Suzuki is attacking expertise; rather, he is noting that expertise often depends on the facility of the expert to reduce the complexities of a situation to a few options for quick resolution or clarification. Expertise, then, may permit the expert to move quickly into and out of a situation, but it also blinds the expert to the swirl of multiplicity around the situation.

I don't know if reductionism is necessary for negotiating reality, but I'm sure it is a convenient habitual practice. The problem is that we forget that it is a fiction, a powerplay to gain physical, intellectual, political, social, religious, aesthetic control over reality, but it is not reality. Students are not students. They are so much more. Both teachers and students must be sensitive to the multiplicity of each other, even as we construct the fictions, the mantras, the formulas that help us through daily life.

This makes me think of the available spectrum of light. We see only a narrow bit of the total spectrum, but it is foolish of us to think that there is nothing else to see. What would we see of the world if we could process the total spectrum? Reductionists foolishly limit the rhizome just to what they can see; however, the rhizome, any rhizome, is infinitely rich, able to elevate and challenge our minds. The available light spectrum is, of course, sufficient to go to the grocery store or to take a test, but the spectrum is wide, even wider than we suspect. What could we see at wavelength -1?

We territorialize the rhizome, perhaps we must, but we must always be ready to follow the deterritorialization. As Deleuze and Guattari note: "It is not enough to say, 'Long live the multiple.' … The multiple must be made, not by always adding a higher dimension, but rather in the simplest of ways, by dint of sobriety, with the number of dimensions one already has available—always n - 1 (the only way the one belongs to the multiple: always subtracted). Subtract the unique from the multiplicity to be constituted; write at n - 1 dimensions. A system of this kind could be called a rhizome" (ATP, 6).

Reductionism always leads to impotence, to the dryzome of the thing being reduced. Reduction of a frog to its constituent parts with a scalpel always kills the frog. Reduction of the frog with language conceals fifty million years of evolution, ecosystems, and your own education. As Wordsworth noted in his great Ode: "To me the meanest flower that blows can give Thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears." As Pirsig noted in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: "For every fact there is an infinity of hypotheses." All rhizomes proliferate, they wallow in promiscuity, assemble, collapse only to reassemble again. "When rats swarm over each other" (ATP, 7).

All students, all teachers, all systems of knowledge are bounded infinities, are assemblages of rhizomes. In classes, they are legion, infinity compounded infinitely. Writing teachers, then, must accept that any forms are provisional, expedient fictions to perform specific tasks within specific contexts. They are not eternal. The perceptive teacher must be open to the interplay of even the most formalized of structures with students. We must be able to follow the rhizome, "the line of flight or deterritorialization according to which [rhizomes] change in nature and connect with other multiplicities" (ATP, 9). That's where all the fun is.

BRB. LOL.

Wednesday, December 30, 2009

Tuesday, December 29, 2009

Writing the Rhizome Classroom

I spent the morning replying to emails from a colleague. He is concerned about the direction our writing across the curriculum program is taking, and I was trying to answer his concerns. This reminded me that I really must connect all this conversation about rhizomatic structures to the classroom, especially the writing classroom. The theory is fun, but if I cannot make it relevant to an actual classroom, then I must question the usefulness. So what would a classroom as rhizome look like or behave like, especially a writing classroom?

Let's start where Deleuze and Guattari start, with connectivity and heterogeneity. "Any point of a rhizome can be connected to anything other, and must be. This is very different from the tree or root, which plots a point, fixes an order" (ATP, 7). The principles of connectivity and heterogeneity totally overturn any form of hierarchical command and control structure which ranks, orders, fixes, and names all points within the hierarchy and which determines which points are inside the hierarchy and which are outside.

Actually, the rhizome does not overturn hierarchy. Rhizome does not contest or overpower hierarchy in any way; rather, it simply renders hierarchy irrelevant and flows around it. The rhizome Internet, for instance, treats any form of censorship as a fault which it isolates and flows around. The rhizome tree forms a knot around an infestation or a break and continues to grow around the offending wound. From a rhizomatic perspective, then, hierarchy is a wound which attempts to overpower the rhizome. The rhizome, in turn, is a force which attempts to isolate and flow around the wounds of the hierarchy.

Traditionally, a classroom is a hierarchical structure for impressing student minds with sanctioned, authoritative information and skills. The teacher sits at the top of the pyramid and brings all value to the class. The teacher represents the gatekeeper, determining who is in the class, within the hierarchy, and who is not. Especially at lower grades, the teacher censors the connectivity of students to anyone or anything other than the teacher and the teacher's information, thus violating the rhizomatic principle that any student of a rhizome class can be connected to anything other, and must be. (This certainly means that students must be able to connect to, be in conversation with, the other students in the class, and not only to the teacher, but it also means that students must be able to connect to anything other. Any point in a rhizome can connect not only to any other point in the rhizome but to anything other. In the universe.) The teacher signifies who is an A, who is a B, a C, a D, and an F student. The teacher determines which information, which behaviors, and which activities are valid and which are not. In the hierarchical class, the teacher represents all the power, ultimately of the State or the Academy, and the student is pressed into shape—is signified, named—by that Power.

A rhizomatic classroom is in/different, even when it adopts hierarchical structures for a time. In a rhizomatic classroom, the teacher is one point among others, not the only point with any power, sitting smugly, angrily, fearfully, or benignly at the top of the pyramid. The teacher is one learner among other learners. We hear this often today in the expression that we teachers should move from playing the sage on the stage to the guide on the side, a glib mnemonic that captures, as it also obscures, the shift from command-and-control power structures to connect-and-collaborate force structures. The teacher is one force among others. The teacher's information is one force among others. The teacher may carry greater force by dint of size, learning, and experience, but the students also carry forces from their own knowledge, skills, and experience, and they, too, exert force on each other and on the teacher as the teacher exerts force on them. They all become a rhizomatic solar system or galaxy, perhaps with some bodies exerting more or less gravitational force than others, but with all of them exerting some gravitational pull on all others, and even if remotely, on all other things in the universe. There is no rank order or fixed position in the rhizomatic classroom, though there can be a coherent dance and interplay. In the rhizomatic solar system, we planets find a trajectory and path because of the force of the Sun's gravitational pull, but the Sun finds its own trajectory and path, in part, because of our gravitational pull on it. And we all planets, moons, and Sun stay in our dance because of our gravitational pull each on all the others. Power, then, works in one direction in one way to create something dead, a dryzome. Force works in all directions in all ways to create something living and beautiful, a rhizome.

As a writing teacher, then, I may exert more force as a more experienced and capable writer (though I have been fortunate to have students whose writing force equaled or exceeded my own), but my colleagues/students also exert their own forces. My role is to engage those forces, dance with them, and intensify them before they spin out of my orbit to engage other forces.

My job is not to determine who/what is in the class and who/what is not. Indeed, our class blogs, wikis, chats, textings, aggregators, etc. have enabled more connections to more people, more languages, and more systems of knowledge than we have wit to comprehend. We connect to any person, any topic, any knowledge, any language that we can engage.

My job is not to signify and rank order students. Rather, my job is to help them determine what forces (what assemblages that they muster together in written language, what texts) work well among other forces (audiences and texts and knowledge assemblages) and what texts do not work well. Why POS works so well in this text among these other texts and readers and yet does not work so well in this text with these readers. LOL.

My job is not to censure or sanction knowledge, but to explore knowledge and to develop an eye for what works well and what doesn't, what plays well and what plays less well and for whom. LOL.

My task is to facilitate a beautiful dance in written language, to "write, form a rhizome, increase your territory by deterritorialization" (ATP, 11). As Deleuze and Guattari say: "We're tired of trees. We should stop believing in trees, roots, and radicles [hierarchies]. They've made us suffer too much. All of arborescent culture is founded on them, from biology to linguistics. Nothing is beautiful or loving or political aside from underground stems and aerial roots, adventitious growths and rhizomes" (ATP, 15). I have no State power to appeal to, no State regime of knowledge to pass along, no authoritative and blessed mother tongue. Writing always works through collective assemblages of enunciation. "There is no language in itself, nor are there any linguistic universals, only a throng of dialects, patois, slangs, and specialized languages. There is no ideal speaker-listener, any more than there is a homogeneous linguistic community" (ATP, 7).

BRB

Let's start where Deleuze and Guattari start, with connectivity and heterogeneity. "Any point of a rhizome can be connected to anything other, and must be. This is very different from the tree or root, which plots a point, fixes an order" (ATP, 7). The principles of connectivity and heterogeneity totally overturn any form of hierarchical command and control structure which ranks, orders, fixes, and names all points within the hierarchy and which determines which points are inside the hierarchy and which are outside.

Actually, the rhizome does not overturn hierarchy. Rhizome does not contest or overpower hierarchy in any way; rather, it simply renders hierarchy irrelevant and flows around it. The rhizome Internet, for instance, treats any form of censorship as a fault which it isolates and flows around. The rhizome tree forms a knot around an infestation or a break and continues to grow around the offending wound. From a rhizomatic perspective, then, hierarchy is a wound which attempts to overpower the rhizome. The rhizome, in turn, is a force which attempts to isolate and flow around the wounds of the hierarchy.

Traditionally, a classroom is a hierarchical structure for impressing student minds with sanctioned, authoritative information and skills. The teacher sits at the top of the pyramid and brings all value to the class. The teacher represents the gatekeeper, determining who is in the class, within the hierarchy, and who is not. Especially at lower grades, the teacher censors the connectivity of students to anyone or anything other than the teacher and the teacher's information, thus violating the rhizomatic principle that any student of a rhizome class can be connected to anything other, and must be. (This certainly means that students must be able to connect to, be in conversation with, the other students in the class, and not only to the teacher, but it also means that students must be able to connect to anything other. Any point in a rhizome can connect not only to any other point in the rhizome but to anything other. In the universe.) The teacher signifies who is an A, who is a B, a C, a D, and an F student. The teacher determines which information, which behaviors, and which activities are valid and which are not. In the hierarchical class, the teacher represents all the power, ultimately of the State or the Academy, and the student is pressed into shape—is signified, named—by that Power.

A rhizomatic classroom is in/different, even when it adopts hierarchical structures for a time. In a rhizomatic classroom, the teacher is one point among others, not the only point with any power, sitting smugly, angrily, fearfully, or benignly at the top of the pyramid. The teacher is one learner among other learners. We hear this often today in the expression that we teachers should move from playing the sage on the stage to the guide on the side, a glib mnemonic that captures, as it also obscures, the shift from command-and-control power structures to connect-and-collaborate force structures. The teacher is one force among others. The teacher's information is one force among others. The teacher may carry greater force by dint of size, learning, and experience, but the students also carry forces from their own knowledge, skills, and experience, and they, too, exert force on each other and on the teacher as the teacher exerts force on them. They all become a rhizomatic solar system or galaxy, perhaps with some bodies exerting more or less gravitational force than others, but with all of them exerting some gravitational pull on all others, and even if remotely, on all other things in the universe. There is no rank order or fixed position in the rhizomatic classroom, though there can be a coherent dance and interplay. In the rhizomatic solar system, we planets find a trajectory and path because of the force of the Sun's gravitational pull, but the Sun finds its own trajectory and path, in part, because of our gravitational pull on it. And we all planets, moons, and Sun stay in our dance because of our gravitational pull each on all the others. Power, then, works in one direction in one way to create something dead, a dryzome. Force works in all directions in all ways to create something living and beautiful, a rhizome.

As a writing teacher, then, I may exert more force as a more experienced and capable writer (though I have been fortunate to have students whose writing force equaled or exceeded my own), but my colleagues/students also exert their own forces. My role is to engage those forces, dance with them, and intensify them before they spin out of my orbit to engage other forces.

My job is not to determine who/what is in the class and who/what is not. Indeed, our class blogs, wikis, chats, textings, aggregators, etc. have enabled more connections to more people, more languages, and more systems of knowledge than we have wit to comprehend. We connect to any person, any topic, any knowledge, any language that we can engage.

My job is not to signify and rank order students. Rather, my job is to help them determine what forces (what assemblages that they muster together in written language, what texts) work well among other forces (audiences and texts and knowledge assemblages) and what texts do not work well. Why POS works so well in this text among these other texts and readers and yet does not work so well in this text with these readers. LOL.

My job is not to censure or sanction knowledge, but to explore knowledge and to develop an eye for what works well and what doesn't, what plays well and what plays less well and for whom. LOL.

My task is to facilitate a beautiful dance in written language, to "write, form a rhizome, increase your territory by deterritorialization" (ATP, 11). As Deleuze and Guattari say: "We're tired of trees. We should stop believing in trees, roots, and radicles [hierarchies]. They've made us suffer too much. All of arborescent culture is founded on them, from biology to linguistics. Nothing is beautiful or loving or political aside from underground stems and aerial roots, adventitious growths and rhizomes" (ATP, 15). I have no State power to appeal to, no State regime of knowledge to pass along, no authoritative and blessed mother tongue. Writing always works through collective assemblages of enunciation. "There is no language in itself, nor are there any linguistic universals, only a throng of dialects, patois, slangs, and specialized languages. There is no ideal speaker-listener, any more than there is a homogeneous linguistic community" (ATP, 7).

BRB

Wednesday, December 23, 2009

The Function of Writing

Our interest in writing should be on what it does rather than what it means, the physical rather than the spiritual: "As an assemblage, a book has only itself, in connection with other assemblages and in relation to other bodies without organs. We will never ask what a book means, as signified or signifier; we will not look for anything to understand in it. We will ask what it functions with, in connection with what other things it does or does not transmit intensities, in which other multiplicities its own are inserted and metamorphosed, and with what bodies without organs it makes its own converge" (4). This is the point at which writing connects with both play and work. Both play and work are doing something, usually with others. Thus, we cease to look at writing as an artifact to be examined and deconstructed or as an expression of an individual mind to be understood or as a reflection of the world to be interpreted; rather, writing is an assemblage of energy and force arising out of other assemblages of energy and force and interacting with yet other assemblages of energy and force. It is the interaction of those assemblages, the interplay or inter-work done by the writing, that should interest us. We should ask what other assemblages of writing this writing interplays with, how it acts upon those assemblages and is, in turn, acted upon by them: what assemblages of commerce, thought, government, religion, or society this writing interplays with and how it acts upon those assemblages and how it is, in turn, acted upon by them. As an assemblage of energy, writing is a billiard ball of approximate size and shape struck by a cue of approximate size and shape with approximate force in an approximate direction on an approximate table of approximate size, shape, density, and level amongst other balls of approximate size, density, and shape in an approximate arrangement. Our interest is to watch the progress of the ball, how it strikes the rails and other balls, how it paces along, strikes, sheers, veers, and rolls, how it rearranges the table in its progress.

Now imagine an infinitely large table curving away forever with balls rolling in and out as they are struck by other cues with lesser or greater force and as the table curves, drops, and sheers this way or that, and then imagine a multi-dimensional table, or plane, or field, with balls of different size and intensities, weight, gravitational pull, and illumination, extending in bounded infinity, out through interstellar space or inside your head, and you begin—or at least, I begin—to capture a sense of an essay, a story, a novel, a book as a rhizome stretching, pulling, pushing, merging, sheering its way through other systems of energy in a marvelous dance of light. "This little light of mine, I'm gonna let it shine," but only amongst all the other lights, building intensity, fading, interplaying, a dance of lights.

This note is my little light. It arises from the light of A Thousand Plateaus by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, specifically from the first chapter, "Introduction: Rhizome," of that book. It also arises from my own education, my own reading, the history of the United States, my marriage, my two sons, my vacation in the Bahamas where it is written, my impatience with the people waiting to go to the beach, my own practice of writing, my knowledge of note-taking and essays, and from infinitely more assemblages; and even now, as merely a faint light that serves only to illuminate my own thinking about writing and rhizomes, the level of this note's interplay, its intensity, is almost more complex than I can imagine as it careens and arcs through the rhizome of my own mind, striking chords with other assemblages of ideas, desires, emotions, plans, intentions, images, and doggerel. God forbid that I should put this on my blog and that others should read it, or that I should incorporate some of these thoughts in a presentation that I may make in Feb, 2010, at the Southern Humanities Conference in Asheville, NC. Who knows what weird scenes inside the gold mine may emerge if it should strike a chord, elevate an intensity, in the writing or thought or presentation of some other. Who can tell what bits of 2009, Christmas-time Bahamas may emerge in the cold hills of North Carolina by way of 1980s France. This single quark emerging from a collider cloud is already leaving traces of its path, and while it is most likely to lose its singular identity and traceability in some other writing or presentation, it is now emerged and is now in interplay with other systems, other assemblages. At present, it is just a note in TextEdit on my MacBook Pro laptop, but soon—or so I intend—a post to my blog, when I can reconnect to the Net. I can infuse, for more reasons than I have wit or clarity to enumerate, more energy into this little light of mine to see where it goes. Or not.

My interest in this bit of writing is its effects, what it does, with how well it plays or works, with whether or not it builds in intensity or is subsumed into some other assemblage of thought, or writing, or presentation, or blog, or glass of wine, or day on the beach. Have I struck it well? Does it have impulse and energy, a promising trajectory? Is it likely to go somewhere, to resonate, intensify? And, anticipating North Carolina, is this writing, this note, play or work? It feels like play just now, and I'm most interested in seeing how well it plays, or works, with other ideas I'm forming about rhizomes and writing, but is this just quibbling? Is it not work? I'm vacationing in the Bahamas, so some of the people here—my family, a sheer force against me (next to, not necessarily opposed to, but perhaps that, too)—think I am working and definitely not playing. They are waiting for me—a different assemblage with different energy decidedly disinterested in French philosophy and obscure plant reproduction—but they won't wait for long. I can feel their energy even as the force of Deleuze and Guattari is fading. What a strange thing writing is. I think I'll go to the beach for now.

But later, I'll have to think/write more about the distinctions between play and work. This note is both, but what does that mean? Deleuze and Guattari say not to ask that question of a text, do not ask what it means. So what is the function? What does it do? Will this note function differently as work than as play? That's promising.

Footnote at time of posting: As it turns out, I didn't make it to the beach, but what the hell! I'm in the Bahamas and life is wonderful.

Now imagine an infinitely large table curving away forever with balls rolling in and out as they are struck by other cues with lesser or greater force and as the table curves, drops, and sheers this way or that, and then imagine a multi-dimensional table, or plane, or field, with balls of different size and intensities, weight, gravitational pull, and illumination, extending in bounded infinity, out through interstellar space or inside your head, and you begin—or at least, I begin—to capture a sense of an essay, a story, a novel, a book as a rhizome stretching, pulling, pushing, merging, sheering its way through other systems of energy in a marvelous dance of light. "This little light of mine, I'm gonna let it shine," but only amongst all the other lights, building intensity, fading, interplaying, a dance of lights.

This note is my little light. It arises from the light of A Thousand Plateaus by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, specifically from the first chapter, "Introduction: Rhizome," of that book. It also arises from my own education, my own reading, the history of the United States, my marriage, my two sons, my vacation in the Bahamas where it is written, my impatience with the people waiting to go to the beach, my own practice of writing, my knowledge of note-taking and essays, and from infinitely more assemblages; and even now, as merely a faint light that serves only to illuminate my own thinking about writing and rhizomes, the level of this note's interplay, its intensity, is almost more complex than I can imagine as it careens and arcs through the rhizome of my own mind, striking chords with other assemblages of ideas, desires, emotions, plans, intentions, images, and doggerel. God forbid that I should put this on my blog and that others should read it, or that I should incorporate some of these thoughts in a presentation that I may make in Feb, 2010, at the Southern Humanities Conference in Asheville, NC. Who knows what weird scenes inside the gold mine may emerge if it should strike a chord, elevate an intensity, in the writing or thought or presentation of some other. Who can tell what bits of 2009, Christmas-time Bahamas may emerge in the cold hills of North Carolina by way of 1980s France. This single quark emerging from a collider cloud is already leaving traces of its path, and while it is most likely to lose its singular identity and traceability in some other writing or presentation, it is now emerged and is now in interplay with other systems, other assemblages. At present, it is just a note in TextEdit on my MacBook Pro laptop, but soon—or so I intend—a post to my blog, when I can reconnect to the Net. I can infuse, for more reasons than I have wit or clarity to enumerate, more energy into this little light of mine to see where it goes. Or not.

My interest in this bit of writing is its effects, what it does, with how well it plays or works, with whether or not it builds in intensity or is subsumed into some other assemblage of thought, or writing, or presentation, or blog, or glass of wine, or day on the beach. Have I struck it well? Does it have impulse and energy, a promising trajectory? Is it likely to go somewhere, to resonate, intensify? And, anticipating North Carolina, is this writing, this note, play or work? It feels like play just now, and I'm most interested in seeing how well it plays, or works, with other ideas I'm forming about rhizomes and writing, but is this just quibbling? Is it not work? I'm vacationing in the Bahamas, so some of the people here—my family, a sheer force against me (next to, not necessarily opposed to, but perhaps that, too)—think I am working and definitely not playing. They are waiting for me—a different assemblage with different energy decidedly disinterested in French philosophy and obscure plant reproduction—but they won't wait for long. I can feel their energy even as the force of Deleuze and Guattari is fading. What a strange thing writing is. I think I'll go to the beach for now.

But later, I'll have to think/write more about the distinctions between play and work. This note is both, but what does that mean? Deleuze and Guattari say not to ask that question of a text, do not ask what it means. So what is the function? What does it do? Will this note function differently as work than as play? That's promising.

Footnote at time of posting: As it turns out, I didn't make it to the beach, but what the hell! I'm in the Bahamas and life is wonderful.

Monday, November 16, 2009

Connectivity Two

Well, the very first characteristic of a rhizome stopped me, and I had to start reading again. In what sense did Deleuze and Guattari mean that "any point of a rhizome can be connected to anything other, and must be" (Thousand Plateaus, 7)? I have a hint of an answer, and I'm working on some other answers, but keep in mind that I am not suggesting that what I say here is what DnG meant when they wrote the above comment. I don't know what they meant, and in some ways, their meaning is irrelevant to me. All I want to talk about—perhaps all I can talk about—is how I interpret what they say. Here's one way:

I think initially I was stymied by my assumption that DnG were saying any point of a rhizome can be directly and simultaneously connected to any other point without any intervening or intermediary points. My mechanistic view of physical reality balked at this, or in DnG's terms, I was trapped in arborescent thinking. In aborescent, or hierarchical, structures, each node occupies a fixed point in the overall structure and connects directly only to those nodes immediately above and below it. Its relation to all other nodes in the structure are mediated, and thus controlled, by the nodes through which it must pass in order to connect and communicate to those remote nodes. Moreover, two points cannot occupy the same space. Arborescent thinking has a very strict economy: one point, one space. A point can occupy only one space, and no two points can occupy the same space—a place for everything, and everything in its place. Any point is responsible for the points below it and responsible to the point above it.

Arborescent thinking, then, creates a rigidly delineated arrangement of any thing, physical or mental. Rhizome thinking is different, though it can incorporate arborescent thinking (Arborescent thinking does not include rhizomes, however). In a rhizome way of thinking, no given point is fixed in any given place. Rather, a point is a nexus of potential places, properties, trajectories, and speeds, a swelter of probabilities that emerge and shift as the point interacts with the field of other points. Moreover, all those points are exerting some influence, some connection, however small, on every other point in the field, all at the same time. And the field is ultimately very large: the entire Universe. Everything is, in fact, connected to every other thing.

Everything, then, is a shimmering potential of probability that emerges into our consciousness for an instant and then arcs on to some other expression. Nothing is static, nothing stays in its place. No place for anything, and nothing in its place.

Well, maybe.

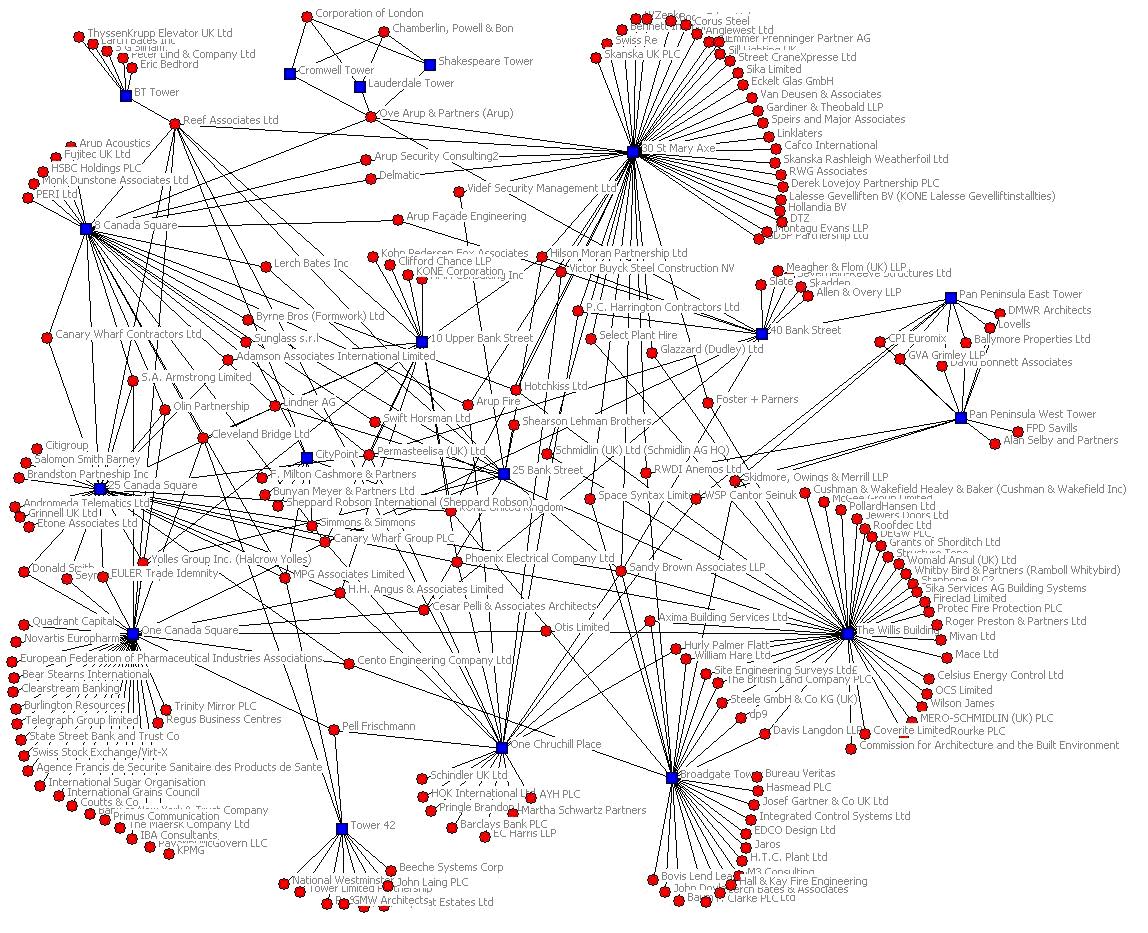

This connection of any one point to all other points is easy to see in digital information, where any piece of data can easily be connected to any other piece of data. For instance, at Amazon readers are constantly applying new tags to books. Indeed, any book in Amazon can have as many tags, identifiers, as people wish to give it. Thus, Deleuze and Guattari's A Thousand Plateaus need no longer be filed in a hierarchical taxonomy under French philosophy, but can be filed as well under modern psychology, poststructuralism, friends of Michael Foucault, stuttering, and weed management. DnG can be connected to most any idea that any reader, however deranged or sane, can imagine.

These connections are hypertext, and they are magical. I'll let Michael Wesch's marvelous video say it for me again:

I think initially I was stymied by my assumption that DnG were saying any point of a rhizome can be directly and simultaneously connected to any other point without any intervening or intermediary points. My mechanistic view of physical reality balked at this, or in DnG's terms, I was trapped in arborescent thinking. In aborescent, or hierarchical, structures, each node occupies a fixed point in the overall structure and connects directly only to those nodes immediately above and below it. Its relation to all other nodes in the structure are mediated, and thus controlled, by the nodes through which it must pass in order to connect and communicate to those remote nodes. Moreover, two points cannot occupy the same space. Arborescent thinking has a very strict economy: one point, one space. A point can occupy only one space, and no two points can occupy the same space—a place for everything, and everything in its place. Any point is responsible for the points below it and responsible to the point above it.

Arborescent thinking, then, creates a rigidly delineated arrangement of any thing, physical or mental. Rhizome thinking is different, though it can incorporate arborescent thinking (Arborescent thinking does not include rhizomes, however). In a rhizome way of thinking, no given point is fixed in any given place. Rather, a point is a nexus of potential places, properties, trajectories, and speeds, a swelter of probabilities that emerge and shift as the point interacts with the field of other points. Moreover, all those points are exerting some influence, some connection, however small, on every other point in the field, all at the same time. And the field is ultimately very large: the entire Universe. Everything is, in fact, connected to every other thing.

Everything, then, is a shimmering potential of probability that emerges into our consciousness for an instant and then arcs on to some other expression. Nothing is static, nothing stays in its place. No place for anything, and nothing in its place.

Well, maybe.

This connection of any one point to all other points is easy to see in digital information, where any piece of data can easily be connected to any other piece of data. For instance, at Amazon readers are constantly applying new tags to books. Indeed, any book in Amazon can have as many tags, identifiers, as people wish to give it. Thus, Deleuze and Guattari's A Thousand Plateaus need no longer be filed in a hierarchical taxonomy under French philosophy, but can be filed as well under modern psychology, poststructuralism, friends of Michael Foucault, stuttering, and weed management. DnG can be connected to most any idea that any reader, however deranged or sane, can imagine.

These connections are hypertext, and they are magical. I'll let Michael Wesch's marvelous video say it for me again:

Wednesday, November 4, 2009

The Rhizome: Connectivity

In Internet: Towards a Holistic Ontology, Chuen-Ferng Koh says that Deleuze and Guattari identify six characteristics of rhizomes and that these six characteristics should rightly be considered simultaneously so that "they can proliferate in the reader's mind" as a whole. Clearly, one should avoid the tendency to bifurcation in making these intrinsic characteristics of the rhizome distinct from one another and from the rhizome. I admit that I am not clever enough to do that yet. Anyway, the six characteristics in a list are (lifted from the web site Capitalism and Schizophrenia):

How is this possible?

- Connectivity – the capacity to aggregate by making connections at any point on and within itself.

- Heterogeneity – the capacity to connect anything with anything other, the linking of unlike elements

- Multiplicity – consisting of multiple singularities synthesized into a “whole” by relations of exteriority

- Asignifying rupture – not becoming any less of a rhizome when being severely ruptured, the ability to allow a system to function and even flourish despite local “breakdowns”, thanks to deterritorialising and reterritorialising processes

- Cartography – described by the method of mapping for orientation from any point of entry within a "whole", rather than by the method of tracing that re-presents an a priori path, base structure or genetic axis

- Decalcomania – forming through continuous negotiation with its context, constantly adapting by experimentation, thus performing a non-symmetrical active resistance against rigid organization and restriction.

How is this possible?

Tuesday, November 3, 2009

Enter the Rhizome: Non-duality

My good friend Dan Jaeckle introduced me to the concept of the rhizome as first expressed by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari in their 1987 book A Thousand Plateaus, the second volume of their two volume work Civilization and Schizophrenia. I do not presume to be a scholar of French philosophy, nor do I presume to understand Deleuze and Guattari very well; however, the rhizome has captured my imagination as a marvelous description of the structures that I have been calling networks. I have been writing about networks for the past two years, and basically, I have been contrasting them to hierarchies. The gist of my argument has been that, in response to modern technology in general and information technology in particular, humankind is undergoing a shift from hierarchy as the dominant mode for structuring human reality to networks as the dominant mode. This shift is as deep and as extensive a shift as humankind has ever undergone, and it will change everything.

However, I have for sometime felt an uneasiness with trying to say all that I wanted to say about this new structure with the term network. I've not been systematic enough in my thinking to say what my uneasiness was all about, other than that network didn't seem to capture just what I meant. Rhizome may be the concept I'm looking for. Whether it captures it all or not, I cannot yet say, but I'm already convinced that it will expand and sharpen my ability to speak about the structures that are coming to dominate the way people think, communicate, and organize their affairs.

I have already corrected one error in my thinking: rhizomes (or networks) are not the opposite of hierarchies, or as Chuen-Ferng Koh says in Internet: Towards a Holistic Ontology, "It is important not to see the rhizome in binary opposition to the tree … The concept of the rhizome was set up precisely to challenge dichotomous branching."

Rhizomes are inclusive of hierarchies. Hierarchies, however, do not include rhizomes, at least not formally. I think it certain that rhizomes have existed in the most rigid of hierarchical structures throughout history, but on a clandestine, ad hoc, submerged basis that is almost never recognized by the power structure of the hierarchy and never sanctioned. Indeed, one of the formal characteristics of hierarchies is that they are exclusive of all that is not within the hierarchy, and they invest great resources in marking the boundaries between the organization and the rest of the world. Hierarchies are always mindful of managing their entry and exit procedures, and they tend to make the barriers to entry and exit rather high.

Rhizomes are not opposite to hierarchies so much as they simply ignore hierarchies, cutting in arcs across hierarchical boundaries and levels, connecting nodes at various levels within the hierarchy to each other and to nodes totally outside the hierarchy. Hierarchies find such connections and collaborations highly disruptive and treasonous.

Rhizomes are indifferent to entry and exit barriers. Whoever will can enter the rhizome, and whoever won't can exit. In either case, the rhizome is largely unaffected. Its formal characteristics persist.

However, I have for sometime felt an uneasiness with trying to say all that I wanted to say about this new structure with the term network. I've not been systematic enough in my thinking to say what my uneasiness was all about, other than that network didn't seem to capture just what I meant. Rhizome may be the concept I'm looking for. Whether it captures it all or not, I cannot yet say, but I'm already convinced that it will expand and sharpen my ability to speak about the structures that are coming to dominate the way people think, communicate, and organize their affairs.

I have already corrected one error in my thinking: rhizomes (or networks) are not the opposite of hierarchies, or as Chuen-Ferng Koh says in Internet: Towards a Holistic Ontology, "It is important not to see the rhizome in binary opposition to the tree … The concept of the rhizome was set up precisely to challenge dichotomous branching."

Rhizomes are inclusive of hierarchies. Hierarchies, however, do not include rhizomes, at least not formally. I think it certain that rhizomes have existed in the most rigid of hierarchical structures throughout history, but on a clandestine, ad hoc, submerged basis that is almost never recognized by the power structure of the hierarchy and never sanctioned. Indeed, one of the formal characteristics of hierarchies is that they are exclusive of all that is not within the hierarchy, and they invest great resources in marking the boundaries between the organization and the rest of the world. Hierarchies are always mindful of managing their entry and exit procedures, and they tend to make the barriers to entry and exit rather high.

Rhizomes are not opposite to hierarchies so much as they simply ignore hierarchies, cutting in arcs across hierarchical boundaries and levels, connecting nodes at various levels within the hierarchy to each other and to nodes totally outside the hierarchy. Hierarchies find such connections and collaborations highly disruptive and treasonous.

Rhizomes are indifferent to entry and exit barriers. Whoever will can enter the rhizome, and whoever won't can exit. In either case, the rhizome is largely unaffected. Its formal characteristics persist.

Tuesday, October 27, 2009

Homo Ludens: The Nature of Play 2

After outlining the formal characteristics of play, Huizinga narrows his focus to what he calls "the higher forms" of play, a clarification that I take to mean the more formal play—mostly of adults—in more advanced societies. Huizinga then explores the two basic aspects under which we confront the higher forms of play:

Huizinga does not address play as a contest in the introduction.

- as a representation of something

- as a contest for something

Huizinga does not address play as a contest in the introduction.

Monday, October 26, 2009

Homo Ludens: The Nature of Play

It's time to start a new book: Homo Ludens: A study of the play element in culture by Johan Huizinga (New York: Harper & Row, 1970). I have a new job—I am the coordinator for the Quality Enhancement Plan at Albany State University in Albany, GA—and this new book is related to that job. My co-coordinator, Tom Clancy, and I are studying the use of play in promoting writing within a classroom. We think that if students can learn to enjoy writing more then they will write more, perhaps even better. We'll see. Anyway, Homo Ludens appears to be one of the seminal books about play, a very serious, unplayful book about play.

The title of Chapter 1, Nature and Significance of Play as a Cultural Phenomenon, is misleading to me as it suggests that play is a phenomenon of culture, when actually Huizinga says that play precedes culture and that culture is rather a phenomenon of play. "Human civilization has added no essential feature to the general idea of play (19) … In culture we find play as a given magnitude existing before culture itself existed … The great archetypal activities of human society are all permeated with play from the start (22) … The object of the present essay is to demonstrate that it is more than a rhetorical comparison to view culture sub specie ludi" (23). First play and then culture. Play appears to be one of those basic boiling pots of mind and heart out of which we prepare the various stews of culture: law, war, poetry, myth, philosophy, business, religion, and art.

Huizinga carefully limits his discussion of play to its cultural aspects, ignoring psychology and physiology. However, he does criticize psychological and physiological explanations of play that incorrectly assume "that play must serve something which is not play, that it must have some kind of biological purpose" (20). For Huizinga, play is its own justification. People and animals play for the fun of it, and that is sufficient within itself.

He reinforces this notion of play as a discrete and fundamental characteristic of humans and animals when he notes that "this fun-element … characterizes the essence of play. Here we have to do with an absolute primary category of life, familiar to everybody at a glance right down to the animal level" (21). Play is not the opposite of seriousness, for some play is very serious, even deadly serious. It is not comedy, wit, folly, or jest, though it may share elements with those. Play is not an element of the great antitheses of wisdom/folly, truth/falsehood, good/evil, virtue/vice, beauty/ugliness. "The play-concept must always remain distinct from all the other forms of thought in which we express the structure of mental and social life" (25). In the end, then, Huizinga doesn't like any explanations about why we play, but he doesn't given an answer either. Basically, he just says we play because it's fun.

He moves from this magical beginning to note that play must have a mental aspect, and usually not rational. "In acknowledging play you acknowledge mind, for whatever else play is, it is not matter (21) … Play only becomes possible, thinkable, and understandable when an influx of mind breaks down the absolute determinism of the cosmos. The very existence of play continually confirms the supra-logical nature of the human situation" (22).

Once Huizinga has assumed the fundamental nature of play, he begins to describe its formal characteristics:

The title of Chapter 1, Nature and Significance of Play as a Cultural Phenomenon, is misleading to me as it suggests that play is a phenomenon of culture, when actually Huizinga says that play precedes culture and that culture is rather a phenomenon of play. "Human civilization has added no essential feature to the general idea of play (19) … In culture we find play as a given magnitude existing before culture itself existed … The great archetypal activities of human society are all permeated with play from the start (22) … The object of the present essay is to demonstrate that it is more than a rhetorical comparison to view culture sub specie ludi" (23). First play and then culture. Play appears to be one of those basic boiling pots of mind and heart out of which we prepare the various stews of culture: law, war, poetry, myth, philosophy, business, religion, and art.

Huizinga carefully limits his discussion of play to its cultural aspects, ignoring psychology and physiology. However, he does criticize psychological and physiological explanations of play that incorrectly assume "that play must serve something which is not play, that it must have some kind of biological purpose" (20). For Huizinga, play is its own justification. People and animals play for the fun of it, and that is sufficient within itself.

He reinforces this notion of play as a discrete and fundamental characteristic of humans and animals when he notes that "this fun-element … characterizes the essence of play. Here we have to do with an absolute primary category of life, familiar to everybody at a glance right down to the animal level" (21). Play is not the opposite of seriousness, for some play is very serious, even deadly serious. It is not comedy, wit, folly, or jest, though it may share elements with those. Play is not an element of the great antitheses of wisdom/folly, truth/falsehood, good/evil, virtue/vice, beauty/ugliness. "The play-concept must always remain distinct from all the other forms of thought in which we express the structure of mental and social life" (25). In the end, then, Huizinga doesn't like any explanations about why we play, but he doesn't given an answer either. Basically, he just says we play because it's fun.

He moves from this magical beginning to note that play must have a mental aspect, and usually not rational. "In acknowledging play you acknowledge mind, for whatever else play is, it is not matter (21) … Play only becomes possible, thinkable, and understandable when an influx of mind breaks down the absolute determinism of the cosmos. The very existence of play continually confirms the supra-logical nature of the human situation" (22).

Once Huizinga has assumed the fundamental nature of play, he begins to describe its formal characteristics:

- Free: Play is free, "is in fact freedom" (26). It is a superfluous, not required activity that people engage in willingly or not at all.

- Extraordinary: In the sense "that play is not ordinary or real life" (26); rather, it "stands outside the immediate satisfaction of wants and appetites" and is "a temporary activity satisfying in itself and ending there" (27).

- Limited: Play is limited in place and duration. It has a playground and a playtime. "It is played out within certain limits of time and place. It contains its own course and meaning" (28). Hence, its close connection to ritual, which also takes place in a hallowed place and time.

- Orderly: Play "creates order, is order … The least deviation from [order] spoils the game," and hence the connection to aesthetics, for "play has a tendency to be beautiful" (29). All play has rules, and violating the rules ends the game.

- Tense: Play has a tension in that the player is trying to do something well or at least better than another player be it solving a puzzle, hitting a ball, or scoring goals. Play tests our prowess.

- Communal: Play often leads to groups of players or fans who define themselves apart from others, adopting costumes and colors and other secret markers.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)