The third consistent and persistent characteristic of complexity that Preiser finds in the literature is non-homogeneity, or as I prefer to say it, heterogeneity. I did not notice if she explains why she prefers the negative expression rather than the positive, but I prefer the positive, probably because of my reading of Deleuze and Guattari's characteristics of rhizomatic structures which have informed my thinking for years now and which resonate well in Preiser's writing.

In an earlier post, I summarized Preiser's non-homogeneity this way:

Complex systems are comprised of a number of heterogeneous components with multiple, dynamic pathways among them that create rich and diverse interactions which become too complex to calculate. The elements and interrelationships change over time and scale.

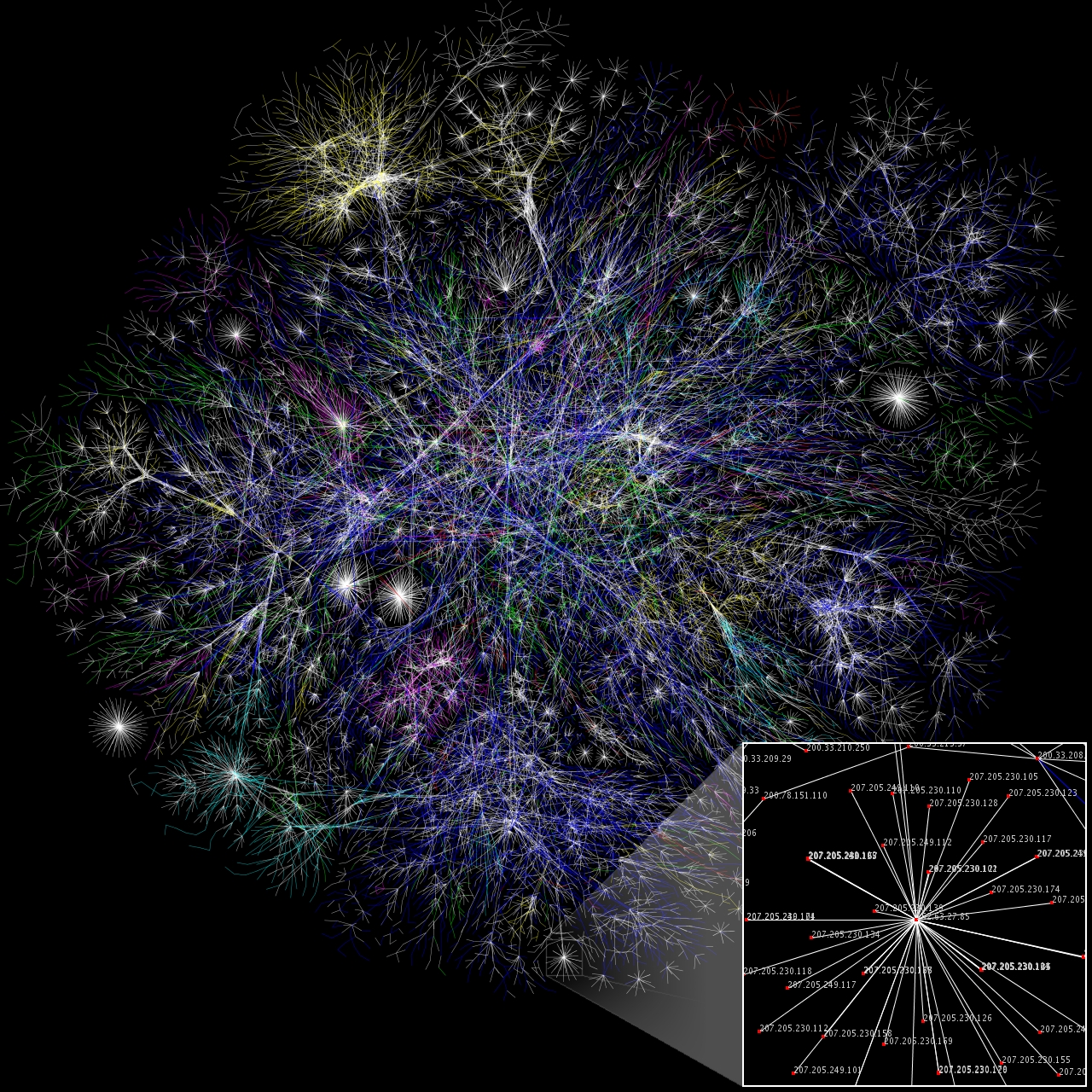

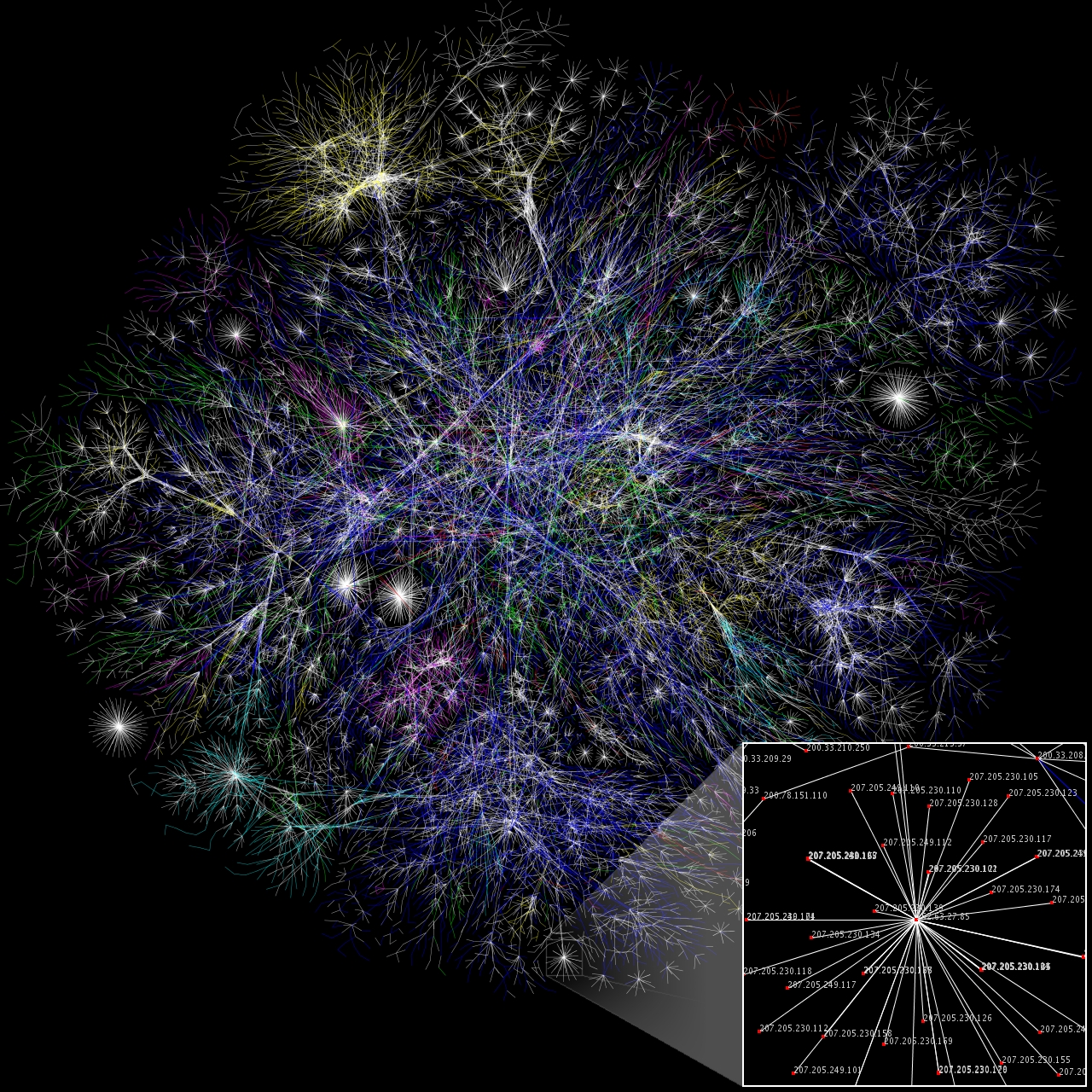

Like Deleuze and Guattari, Preiser joins the concepts of multiplicity and heterogeneity to say that complex systems are made up of a number of distinguishable entities that interact with each other in countless ways to form a functioning entity that itself helps make up an enclosing, functioning entity. So to understand Keith Hamon through the lens of complexity, I must think of myself as comprised of a number of different organs that interconnect with each other along multiple, dynamic pathways that create rich, diverse interactions that are too complex to fully calculate. Moreover, I must think of different scales, so that I see each of my organs -- my lungs, for instance -- as a complex system itself comprised of tissues and cells, which are themselves complex entities comprised of multiple, heterogeneous molecules, which are themselves ... well, you know the drill by now. And I must be able to scale up to see that I, Keith Hamon, am one of the multiple, heterogeneous entities that comprise larger complex systems: my university or my family, for instance. And all of these different entities at the different scales are all interconnected by countless pathways to manage various flows of energy, matter, information, and organization to all the other entities at all scales. For example, consider an image of just one complex system, the Internet:

|

| A Map of the Internet in 2017 |

Of course proximity has its privilege so that entities closer to each other typically exert more influence on each other, but all entities exert some influence on all others, and this complex weave of forces becomes impossible to map. Note that the map of the Internet above does not include the people who connect to all those wires and routers. It doesn't map the software or the content. As complex as it already is, that map is woefully inadequate to explain the Internet. We simply can't reliably trace a single cause to a single effect. This uncertainty helps me understand Covid-19, for instance. We know that the disease starts with a particular virus, but the same virus has such a wide range of interactions with different human and animal hosts. Many don't notice this virus any more than the other viruses inhabiting their bodies. Some become mildly or violently ill. A few die. The explanation for any of these different states depends on more than simply tracking the path of the virus through a specific body.

So what causes someone's death? The virus, of course, is a necessary component of a Covid-19 death, but it is not sufficient to explain that death. A body is a complex system, and its interaction with any external agent such as a virus can be explained only by considering all the various heterogeneous elements and the interconnections among them. It's becoming obvious to me that understanding why one person dies from Covid and another does not demands knowing not only the disposition and interactions of all the person's internal systems (organs, tissues, cells, and the like), but also their external social, economic, political, and religious systems. All of these systems interact to render some people vulnerable and some not, and we are only dimly becoming aware of this complex interaction. We may never understand it fully -- at least, not before the virus moves on to be replaced by another pathogen with a different complex of interactions. And because it's such a complex matrix of interactions from so many different systems, we may never be able to bring sufficient forces in the form of medical and social therapies to bear on everyone's illness. We are not that resourceful or wise.

But I haven't really dealt with heterogeneity. Why should entities in a complex system be different from each other? The short answer is to enhance the resilience and responsiveness of the system to its environment. Because my body has an array of organs and tissues that perform a range of functions, I can better "suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune." (Sorry for that unfortunate comparison. "I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be.") For instance, compare my body to that of slime mold, a relatively simple creature that has very few ways to perceive and to respond to its environment. It can sense its world only in a very narrow range, and it can process and respond to those sensations in even more limited fashion. More complex creatures, including myself, can sense more of the world, process those sensations in more ways, and respond in more ways. This variety makes my complex system more resilient, more likely to survive and thrive.

Of course, my complexity is only relative to the simplicity of the slime mold. Compared to a rock, the slime mold is a quite complex creature. And as I've already noted in a previous post, the simplicity of a rock may be a trick of different time scales. Because rocks perceive, process, and respond to their environment over millenia rather than minutes as I do, then they seem dumb to me. For all I know, rocks might be the geniuses of Earth, and I regret that I will not likely be here when they reveal their plan.

My house has its own complexity: a range of different rooms serving different functions. It has heating and electrical systems that perceive, process, and respond to the environment in different ways to preserve its own integrity and to please its microbiome: me. Moreover, my house is in a neighborhood of heterogeneous homes. My house does not look like my neighbors' houses, as all the houses here were built by different people of different economic status at different times in whatever style and with whatever materials were popular with the owners at the time. Tastes changed and so did the houses.

The variety of houses gives my neighborhood an organic character that contrasts remarkably with the mechanical, cookie-cutter character of the newer subdivisions where all the houses and yards have a homogeneous look and feel. That is an aesthetic judgement on my part, but it explains why I prefer a garden of many plants and flowers rather than a garden of one flower, however beautiful the flower. If a blight attacks my garden of many flowers, then some will survive. If a blight attacks a garden of one flower, the garden dies. Complexity is not only more resilient, but to my eye, it is more beautiful. I celebrate complexity and appreciate its proximity to chaos. That's where all the excitement is.

No comments:

Post a Comment